ALTOONA, Pa. — Super Bowl LI is being played on Sunday at NRG Stadium in Houston, Texas. The stadium, which opened in 2002, sits right next to a far more storied structure, the Houston Astrodome or, as some call it, the “Eighth Wonder of the World.”

Decades of history — architectural, sports and cultural — reside in this domed marvel with a now-uncertain future. In "The Eighth Wonder of the World: The Life of Houston’s Iconic Astrodome," a new book by Robert Trumpbour, associate professor of communications at Penn State Altoona, and Kenneth Womack, dean of the Wayne D. McMurray School of Humanities and Social Sciences at Monmouth University in New Jersey, the authors detail the Astrodome's colorful past.

The book is the winner of the 2017 Dr. Harold and Dorothy Seymour Medal, awarded by the Society for American Baseball Research to honor the best book of baseball history or biography published during the preceding calendar year.

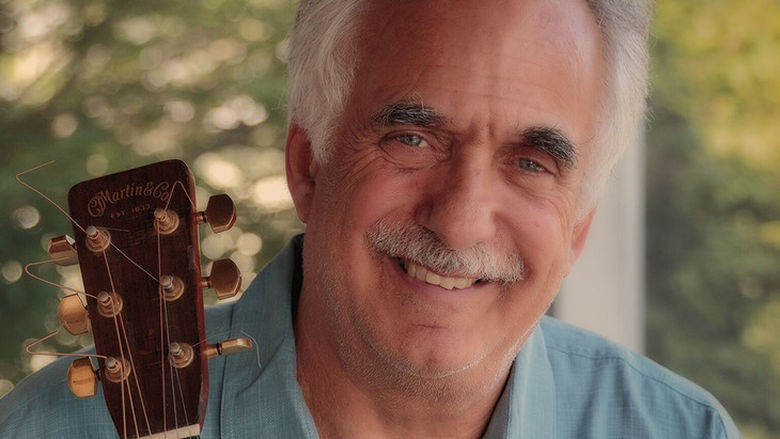

Trumpbour said he and Womack, former professor of English and integrative arts and senior associate dean for Academic Affairs at Penn State Altoona, had been talking about collaborating on the book “for a really long time.” The two men are a good fit for the project — Trumpbour studied stadia for his first book, "New Cathedrals: Politics and Media in the History of Stadium Construction," and said, “My primary research area is how things get built and media campaigns and stadiums.” He also spends time in stadiums; in addition to his teaching duties, he occasionally works as a field producer for Westwood One during NFL games.

Womack’s connection to the Astrodome is much more personal — his grandfather, Kenneth Zimmerman, was the lead engineer on the dome's construction. “The Astrodome and I go back a long way,” he said. “It is almost like a member of the family.”

The idea for the Astrodome started in the 1950s with Judge Roy Hofheinz, a Texas native with a dream to make Houston a world-class city; he is described in the book as “part huckster, part visionary, part fundraiser.” Hofheinz originally envisioned a domed shopping mall before settling on a stadium for a much-longed-for Major League Baseball team. While he was the driving force, it took much collaboration from many parties to build the Astrodome, which opened in 1965.

“It’s a great story about different parts of a city coming together to create a new future for itself,” Womack said. Speaking of his co-author, he said, “Bob has expertise on stadium construction with civic municipalities. At times this was that kind of story, too. Deals had to be made to facilitate bonds in the 1960s.”

When asked to talk about what fascinates him about the Astrodome, Womack starts to sound less like a Beatles expert (which he is) and more like the grandson of a structural engineer. In writing the book, his attention, he said, was on “technologies that didn’t exist that needed to be created.” Having a domed, lamella truss roof with constructional integrity required Zimmerman to devise two specific features, which he named the knuckle column and the star column. The former, according to the book, “flexes, much like a person’s knuckle, toward the center, while remaining outwardly fixed. The knuckle columns exist along the stadium’s roofline, connecting the dome itself to the exterior superstructure.” The star columns, “X-braced steel bents down to the foundation,” work against the forces of wind and gravity. Zimmerman named them “star columns” in a nod to Texas as the Lone Star State.

“A lot of his engineering work was a precursor to what was accomplished with the World Trade Center, dealing with sway, weight, the forces that play on large structures,” Womack explained. “Once you get over a certain height, these forces take over.” Because of these two column designs the building is able to handle environmental changes, important in an area with temperatures over 90 degrees nearly one-third of the year and the annual threat of hurricanes. The engineering innovations have stood the test of time, he said: “The knuckle column is literally moving right now.”

The Astrodome was groundbreaking in more than its construction. The glare from the Lucite roof prevented ballplayers from seeing fly balls, so eventually the roof was painted over. But without sunshine the grass inside the Astrodome died. This brought about the invention of Astroturf.

Trumpbour has his own history with stadiums; he spent his childhood going to ballgames at Shea Stadium and Yankee Stadium and was already studying his future research subject: “When I was a young kid, Shea was new and I got to see the contrast between the new and the old.” But that was a far cry from the Astrodome, which he said was “the transition to opulence and luxury, a game-changer as to how people conceptualized live entertainment, and one of the reasons people have gotten excited about it. For me, someone who studies stadiums in general and the different types of stadiums, the Astrodome is a unique building from a historic perspective.”

The future of the Astrodome, which closed in 2002, is uncertain, but both authors have hope that it will be revived in some form. As Womack said, “it seems ridiculous to tear down something that can be repurposed in numerous practical ways. There are a lot of smart things that city leaders can do.” Trumpbour echoes his thoughts, noting its longevity — “it’s lasted a lot longer than most” — and the feeling of pride the Astrodome brings for Houstonians. The Eighth Wonder of the World may become a parking garage, with retail and commercial space, but the original will always have a place in history.