This dialog contains the full navigation menu for this site.

Coaching a sports team takes energy and enthusiasm. Players need instruction and guidance, encouragement, and motivation. Pamela Snyder Etters utilizes all these skills when coaching Penn State Altoona’s women’s soccer team. Off the playing field, those same skills get a workout as Etters leads Murals Talk, an art project aiming to impact people and communities in positive ways. Her most recent work involved a very large mural in San Jose, Costa Rica.

While Etters is an experienced artist, with her murals on display in places such as Altoona and Milton, PA, to name a few, she is also an educational advocate for the arts. “My full-time job is executive director for Citizens for the Arts in Pennsylvania,” she says. “I am essentially the arts advocacy leader in the state. I listen to and relay information to state legislators. We try to promote positive changes in policy supporting the sector and increased funding.”

Legislation, though it can be effective, is not the only path to “positive change.” Getting out into the world and working with people on art projects creates a very personal, potentially life-changing experience for everyone involved. Etters’s work on what has become the Murals Talk Foundation gives her those personal interactions.

Etters brings people together with “mural exchanges,” the sharing of art and culture between people who would not otherwise know each other. The first event, in 2012–13, included sixth graders at Juniata Gap Elementary School in Altoona and fifth graders at Tangier Smith Elementary School in Mastic Beach, Long Island, which had been hit hard by Hurricane Sandy. Awareness of the devastation the children in Long Island were experiencing moved the Juniata Gap students to create a mural as a gift to lift their spirits. When the mural was presented to the New York students, they created their own mural to give in return. The two groups eventually met on Skype and shared their experiences. The full story can be found on the Murals Talk website.

The following year brought the first international mural exchange when the Penn State Altoona women’s soccer team traveled to Costa Rica. The tour group they used arranges sports tournaments that include experiencing local culture. Participants are also “required to give an hour of community service,” shared Etters, an experience she says is “worth so much.”

To fulfill the community service requirement, Etters first took members of the Penn State Altoona Women’s soccer team to Juniata Gap Elementary, where they worked on the first half of a five-foot by eight-foot mural to be shared with a community in Costa Rica. While in Costa Rica, the entire team visited an elementary school in the rainforest, Alajuela Province. “We worked with a school with one or two teachers—it’s almost like homeschooling, with just three or four adults. We talk to the kids and do a lot of games and interactions.”

With Etters’s guidance, the Costa Rican students completed the mini-mural, which was an extension of the initial work done in Altoona. She then left one half of the mural there and brought the other back to Juniata Gap Elementary School, where she talked with the children “about Costa Rica and other cultures and their peers in other countries. They think they have it rough here, and the reality is they do not. Even our level of poor, in most cases, doesn’t touch theirs.”

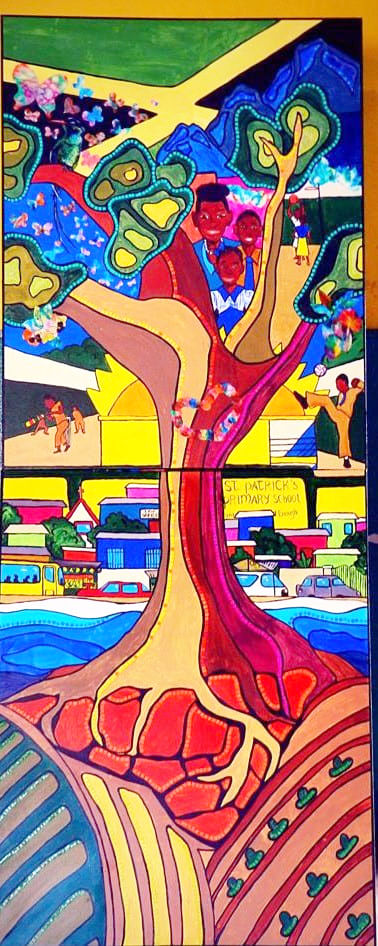

Over the ensuing years, Etters has continued to work with students and the public on mural projects. In 2015 the destination was Kingston, Jamaica, the homeland for then–Penn State Altoona men’s soccer coach Patrick “Moe” Taylor. Students at Juniata Gap Elementary listened to Taylor speak about his childhood and learned about Jamaica before creating a partial mural that Etters and mosaicist Dr. Anju Jolly then took to Jamaica to complete with schoolchildren in Waterhouse, Kingston, Jamaica. They visited the elementary school Moe once attended as a child. “He was truly an inspiration to the children there, as he continues to be to youth here in our region.” The full story is available on the Murals Talk site.

A mural coordinated by Pam Etters, located in the Juniata section of Altoona.

Snyder has also worked on murals locally, such as UPMC Pediatric Care Unit, TLC Childcare, and WeCare (now ProCare) in Altoona, and even moved outside to complete one in Juniata with the help of the community in just twenty-four hours. In 2019 Snyder and her soccer team again brought Costa Rican culture to students at Juniata Gap Elementary and American culture to students in San Carlos, Costa Rica, with a mural exchange. Along for that trip, one that would change her life, was Cierra Rhodes, Penn State Altoona accounting major and soccer player.

“We did a little project with the kids,” Rhodes says. “One school, all different age groups, one teacher, and he was the principal, too!” For the exchange, “we brought a mural with us for them, and we had one for them to fill in. We went into their concrete play area and did soccer games with them, ran around, and played tag. I could communicate with the kids through broken Spanish, the art we created, and mannerisms. I met a little girl at a fruit market, and her name was Cierra, too.”

The flight home was delayed, which gave Rhodes and Etters, who had been Rhodes’s soccer coach on club teams for years, a chance to talk. Rhodes had found the accounting major “boring. It wasn’t me.” She switched to criminal justice because she thought she might like forensic accounting. But then she took a human development and family studies (HDFS) class, and “it had a section on child maltreatment,” she says. During the flight delay, she talked to Etters about making one more change. Etters thought HDFS might be a good major. “I didn’t even know what it was,” Rhodes admits, but after their discussion and some encouragement from Etters, she made the switch.

In 2020 Etters planned another trip to Costa Rica and a new mural project. But—as with everything else in 2020—one year turned into three. In the fall of 2020, Etters and creative partner Jolly arrived in Costa Rica. As she had for the Jamaica trip, Jolly joined after she was persuaded when, as she says, Etters told her, “You will fall in love with the people.”

The beginning of a mural located near the Pacifica Fernandez Elementary School in Costa Rica

The search was on to find a suitable canvas for their next mural. “We looked at several early childhood centers, poor neighborhoods,” Jolly says. Behind an elementary school, they found a wall that “was huge,” she laughs. “I kept focusing on smaller walls.” But “Pam’s spirit is contagious,” and so this wall—over 850 square feet—was chosen. Not only was the potential art space inviting, but also, “these kids were unbelievable. I knew this was where we were going to be.”

Once the site was chosen, Etters and Jolly worked with the students in Pacifica Fernandez Elementary School, which sits adjacent to the chosen wall, to draw things that were important to them. “We talked about what their goals and dreams are and the things that they would like to see change—and what would inspire the change,” Etters says. “Showing partnership and relationships are critical. The core of all of this is education. The most important thing [for these students] is being literate, going to school, and getting an education. We wanted to inspire them.”

Leah Klevan (volunteer from ArtsAltoona), Pam Snyder, Cierra Rhodes, and Anju Jolly with the final mural in Costa Rica

Jolly was moved by the students’ responses. “These kids shared their hopes and dreams,” she says. “They really want to work hard in school. The English language is one of their dreams. They want to grow up and be a doctor, help other people, and be close to their families. Their dreams were so much richer in humanity than wanting a cool car. They wanted things that enrich their lives that we don’t even think about. Here the dream was so simple, yet still very powerful.”

After working with the students, Jolly wasn’t yet settled on a subject matter for the mosaics. But inspiration was about to happen. “We had an afternoon to kill and went to a butterfly park,” she says. “When a butterfly landed on my finger, I knew this was all going to be about butterflies. Butterflies are dreams, hopes, and relationships.”

During their flight home, Etters was already drawing images for the mural on a paper towel. The construction process involved five-foot by fifteen-foot panels of mural cloth laid on a table so she could paint them. “The students are really rooted in their culture,” Etters explains when describing the mural. “Music and dance are important, so the final mural has dancers and a little girl pretending to be one. The Costa Rican flag and soccer players, flora, and fauna are all very important to them—they embrace the fight against global warming. You’ll see that behind the children [in the mural]. They talk about city life and rural life and how farmers are critical. They have one astronaut from Costa Rica. We paid homage to that with the night sky and planets.”

The foliage also provided a landing space for the mosaic butterflies. “A mosaic is made up of little pieces,” Etters says. “Butterflies come in an infinite number of shapes, sizes, colors, and patterns. We like them for their metamorphosis. And everyone considers each butterfly to be beautiful in its own way. The visualization of the little pieces all together makes it hit home even more for these kids. It allows them to think harder about their own metamorphosis and what they could do as they put the pieces of their own lives together.”

The 2020 spring trip was as usual—Etters, Jolly, and a group of six volunteers made the trip to San Jose, Costa Rica, just as rumors of the pandemic were fast spreading, but before widespread concern really set in. The initial purpose of this trip was going to be cleaning and preparing the wall, but much to their surprise, the community (Hatillo 4) had come together to clean and prep the entire wall. “They were very excited about the project and wanted to show us they were grateful for our selecting their community,” says Etters. During this trip, they shared the final design with the students they had worked with months earlier, provided a mural canvas for students to participate in the painting, and installed the first two large panels. The US mural group left Costa Rica, promising to return just three months later to complete the project.

When the pandemic hit, though, the project came to a grinding halt. All the work, plans, and promises now hung in the balance. Etters and Jolly continued to communicate regularly with their Costa Rican partners, ensuring them the plan was simply delayed, and they were dedicated to completing this project!

From inspiration to final construction, in the midst of COVID-19, took four trips to Costa Rica. For the final trip, another group of volunteers went along. Etters carried the mural panels in her backpack. Jolly’s butterflies were cut into two pieces and put in two large suitcases. “I had sixty-some pieces of butterfly, and Pam had over 250 pounds of supplies. But, when Pam unrolled the panels in the school lobby, it was amazing,” Jolly says.

The twelve panels were installed by a crew of seven women, and while the mural finally hung on the wall, there was one more part to this mural project: locals were invited to dip a hand in paint and put their handprint on the mural, “almost like flowers in a field,” says Jolly. “The next day, when we put the butterflies on, the kids brought other people to put on their handprints. The project had gone on for so many years that children who were in fourth grade when it started were now seventh graders.” One father even brought his seven-month-old son to place a handprint.

On dedication day, when the group told the children to “‘tell your parents to come and see the mural, loads and loads of them came—parents, children, babies—everybody came. The line was so long!” Jolly says. “The local municipality came and brought us a Costa Rican flag. They said, ‘we’re so thankful for our friendship with the US.’ It was a great time.”

While the mural, including butterflies, was in place and the handprints added, Etters still wasn’t finished. “There was a daycare center” on the other side of the muraled wall, Jolly relates. “On the very last day, Pam brought a paper towel [with a new design drawn on it]. At seven in the morning, we were painting that other wall. The one extra butterfly went to that wall. So, both sides of the wall got murals.”

Reflecting on her art and the reactions to it, Etters says, “I think that what I enjoy about visual arts—specifically murals—it’s a universal language. Regardless of social, economic, or verbal barriers, you can communicate with people in an enriching way.” And that’s why her organization is called “Murals Talk.”

“We have found that when we talk with impoverished communities, they don’t talk about their future. They don’t say, ‘I’d like to be a lawyer, a veterinarian.’ But when they are given paper and asked to express their goals visually, they will immediately draw what they want to be when they grow up. The process of designing and creating the mural provides a bridge for them to verbalize and put into words their dreams and goals.”

That simple action, Etters observes, helps teachers understand their students’ dreams. For example, a drawing can show a teacher that “‘Jorge wants to be a doctor.’ The teachers can guide them and direct them, they know what these kids are looking for. The kids start to support each other and encourage each other. It’s a tangible difference. Once you empower the teachers, they can use a similar process—have the kids drawing, visualization first, then words—and then building a support system for it.”

Reflecting on the three-year journey, Jolly calls it “the project of a lifetime. We say we are going to enrich their lives, but in reality, they enrich our lives.” Rhodes says that a real highlight was “getting to know people from the community. Everyone was extremely friendly. It made me wish people in the US would take tips from them. Everyone there loves each other.”

Etters’s message is one of optimism and hope, illustrating her commitment to the arts: “People in leadership need to recognize how the arts function as a means to support our mental, physical, and emotional health. Art founded this country. Where would we be without it?”