This dialog contains the full navigation menu for this site.

Anyone who has ever taken a dip into ancestry research knows how quickly a day can pass as one search leads to another, maybe a little bit of history you didn’t know or an interesting story about someone you never met. While she’s not looking for family members, Harriett Gaston, DUS academic adviser at Penn State Altoona, has been doing that type of research as she works to uncover the rich history of African Americans in Blair County.

Harriett Gaston, Coordinator of Minority Programs, Division of Undergraduate Studies

As happens with research projects sometimes, Gaston came to this in a roundabout way. “Local community leader Rev. Paul Johnson and Cummins McNitt, the curator of the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania, wanted to highlight the history of the Great Migration,” she says. African Americans in the early 20th century traveled north “to take on jobs in the industries that needed bodies.” Between 1916 and 1918, in fact, the Pennsylvania Railroad offered free passage north to people who wanted to work for the railroad. Gaston says that Johnson and McNitt “were interviewing local Blacks and recording that and trying to preserve the history.”

Out of their efforts, Gaston says, the African American Heritage Festival of Blair County was born. Begun in 1995 at Garfield Park, the festival moved to the Penn State Altoona campus the following year. “Dr. Jerry Zolten took the initiative to contact the CEO at the time to ask if Penn State Altoona could host the festival.”

“In part because most of the singers and instrumentalists were African American and from local communities, my R&B group, Code Blue, was the first musical group to headline” at the festival, Zolten says. “I fell in love with it. That first one, a deposed king of an African country was there, in a little park in Altoona.” Zolten worked to get the festival moved to the Altoona Campus and that’s when he met Gaston, whom he credits for “her energy and wisdom and know-how, her vision. One of the first guests we had at the festival was David Bradley who wrote The Chaneysville Incident. Harriett also helped bring in performers, like the Southside Steppers.” The festival was held for 21 years but ended “due to a lack of funding.”

From her work with the festival, Gaston says, “I was drafted to be president of the African American Heritage Project.” But it was an encounter at her church that really lit the fire for her dive into African American historical research. “A member of the church I was attending at the time showed me a document of tax property with two people as slaves in 1797 in Tytoona, which is in Sinking Valley. Going back before the county even came into existence—that opened my eyes. Collecting those stories is important.”

A good number of resources for research are easily available and, in Gaston’s case, quite convenient. In addition to online sources, “I used the Blair County Genealogical Society. All this stuff has been gathering—written stories, oral stories on Blacks in this county and before it was a county.” In addition, she searches old newspapers for information. “I have been fortunate to find a number of obituaries that say, ‘they were part of the Underground Railroad.’”

Gaston has a wealth of stories about Underground Railroad activities in the Hollidaysburg area. William Jackson and his father, who were slaves in Virginia, escaped north and were found hiding at Chimney Rocks by local resident David Brown, who was walking his dog. Brown brought the two men into Hollidaysburg, where they stayed with Brown’s family until they found local employment. Four other people, Gaston relates, were also found at Chimney Rocks but they were brought into town and “kept in the jail for safekeeping,” she says. “The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was in place and the assistant DA was given the task of dealing with the runaways.” But, “before he got to the court, someone freed those people and moved them on.”

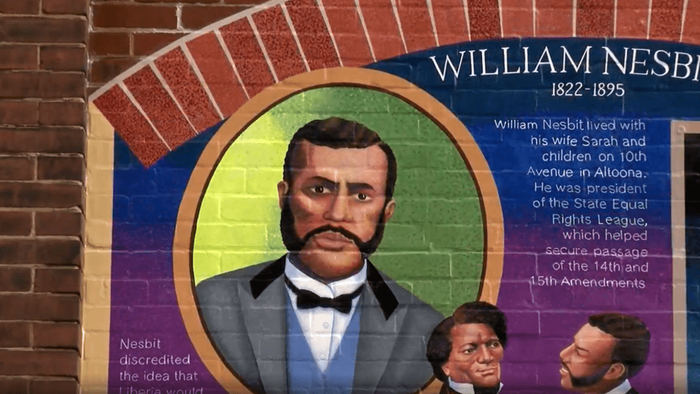

Mural of William Nesbit

Most likely one of the highest-profile African American residents was William Nesbit (1822–95) who, Gaston says, “moved from Carlisle to Hollidaysburg 1843ish, and then to Altoona in the 1850s. He was a barber and he sold wares. He became a notary.” Nesbit was also, according to his obituary, an engineer on the Underground Railroad, working with Bedford County resident Benjamin H. Walker to move former slaves north and to safety. On the national level Nesbit, as president of the Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League, lobbied in Washington for passage of the 14th Amendment. A mural on a wall at Altoona Pipe and Steel honors his memory.

The wealthiest African American in Blair County, while not having any statewide or national recognition, was very well known at the local level—Moses Brown (1827-1916). Gaston lists his accomplishments: “He was a barber and could cook. He opened a restaurant and catering service on Allegheny Street in Hollidaysburg, right down the street from the courthouse. He made and sold ice cream at the Blair County Agricultural Fair and at Lakemont.” Brown also purchased property that had a pond to support both his ice cream and his ice businesses—“still known as Brown’s Pond,” she notes—and land that would become valuable real estate as Sylvan Hills and Blairmont Country Club. While he kept his other businesses going until 1913, Brown retired from the restaurant business in 1887 and passed it to his oldest son, Charles, who had been the first person of color in Pennsylvania to earn a high school diploma when he graduated from Hollidaysburg High in 1881.

“Long before the Altoona Curve [baseball team],” Gaston says, “Pennsylvania Railroad executives wanted to have cricket” and so the PRR built a cricket field on Chestnut Avenue. Since the demand for cricket was not year-round, the field was also used for lawn tennis, football, and even baseball. The Homestead Grays, a legendary team in the Negro leagues with owner/manager Cumberland Posey, played regularly in Altoona. Posey was responsible for bringing the first night game to Altoona—the Kansas City Monarchs and the Homestead Grays played at the cricket field under portable lights.

The stories go on—Gaston's blog is full of articles, photographs, and links about people, businesses, women’s clubs, churches, soldiers, and cemeteries. It’s no wonder that Zolten calls her a “tenacious researcher. She continues to teach me about small aspects of the Black community in Altoona. Every month or two I’d get a collection of newspaper clippings. Everything from the world-famous Fisk Jubilee Singers to other famous gospel groups and jazz and blues artists. She really is some researcher. She finds this stuff and has the good heart to share it.”

Gaston admits that “I don’t have enough time. I would like to write a book,” her goal being “making it accessible to people who want to teach about local black history.” But of course funding is always an issue; she recognizes that she needs “someone with faculty status to get grants.” She would also like to have a secure place to keep the items she has collected, acknowledging, “It would be best if it was housed somewhere other than an attic.”

Gaston has given a number of talks in the area, such as “Ex Slaves Surviving and Thriving in Central PA” in March 2020 at the Hollidaysburg Public Library. An earlier talk at the Tyrone History Museum focused on interviews Gaston did with long-time local resident Minerva Frank about her recollections of an ex-slave named Sarah Shelor who lived in Warriors Mark and was buried there. Zolten introduced Gaston to Frank and says that Frank “told us childhood memories of how she [Shelor] was the midwife for the community. Harriet and I located the grave and took pictures of it.”

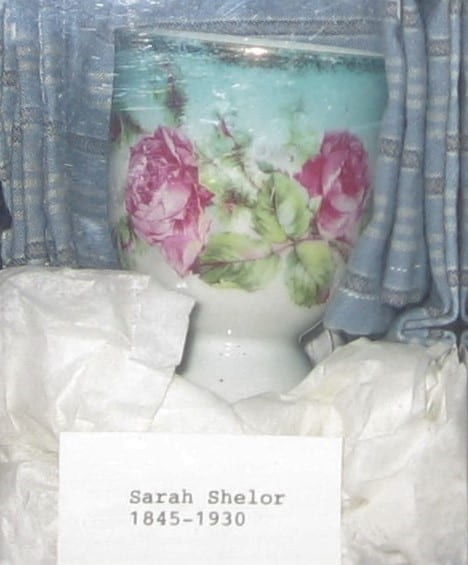

Egg cup belonging to ex-slave Sarah Shelor, a resident of Warriors Mark, PA

Frank also bequeathed to the Blair County African American Heritage Project a small egg cup that had belonged to Shelor. Zolten recollected handing it to Gaston at the African American Festival that year. “Harriet got all teary-eyed and so did I. Next thing I knew people were coming in from around us to touch this object, this talisman, a material connection to slavery and the local African American community. That moment and Harriet’s emotional reaction to it—powerful.”

When Gaston isn’t involved in researching or speaking, she is busy working as the DUS academic adviser at Penn State Altoona. “I advise students exploring majors or transitioning. Maybe a student didn’t take trig in high school or they’re taking courses that are keeping their options open.” She shows them “how to reach out to people like faculty or career services. I’m their guide, their coach.”

While Gaston did not get into this research to find family, she may have anyway. “When I first moved here, a woman came up and said ‘Cousin!’” because they shared a last name. At first Gaston was skeptical but it turns out that the Gaston name can be found in the Claysburg area, including a pitcher for a local baseball team in the 1930s. Of course she had to see if she could find anything. And “after doing research on my family, we may be related. Another part of the Great Migration!”