This dialog contains the full navigation menu for this site.

In a research project, the researcher sets out to answer a question. It may be one part of a larger question—or multiple questions. Dr. Shihui Shen, professor of rail transportation engineering (RTE), and Dr. Hai Huang, associate professor of engineering at Penn State Altoona, are leading a multipronged research project involving recycled plastics, railroad ties, and sensing equipment.

Plastics are everywhere; in the United States and many other countries, it’s impossible to get through a day without contact with them. In 2021, 85 percent of plastics in the United States ended up in a landfill. “We use so many plastics in our daily life that are not biodegradable,” Shen says. “Either it goes to a landfill, it is burned, or it is reused.” The United States used to ship its plastic waste to China but China halted its import waste policy in 2018, which “gives the US a big plastics issue.”

Awareness of the problem has led to a search for solutions. “EPA, DOE, and DOD have had many studies recently on upcycling or recycling plastics to make it more useful in industry,” Shen notes. One of those uses is railroad ties, which “can consume a large quantity of waste plastics. Currently, there is no systematic research on this topic.”

Dalton Yoder at Penn State Altoona’s Student Expo

Three student-researchers are working on the project: senior and RTE major Dalton Yoder at Penn State Altoona and Jubair Ahmad Musazay and Yuliang Zhou, both working on Ph.D.s at Penn State's University Park campus. Shen describes how the group works using a tiered mentoring approach: “the undergraduate student Dalton is mentored by both graduate students and the faculty. The graduate students served as the mentor of the undergraduate and also the mentees of the faculty.”

Yoder describes his research work “in the PSU libraries rooting through the documents and publications on plastic railroad ties.” Specifically, he was looking for “the history of who started it, trying to figure out if anyone had any formulas—anything to give us a head start instead of starting from scratch.” He found “there’s not a lot of data. People were trying it back in the ’90s but not having success. It’s been in limbo the past couple decades.”

Musazay’s focus is on the design formula and testing of railroad ties. As he explains, traditional wood ties have environmental drawbacks because they are treated with chemicals that leach, and they have a vulnerability to termites. Steel ties and concrete ties have their own issues. But making a working railroad tie—no matter the material—is more complicated than just replicating the dimensions of a wood tie. “AREMA [American Railway Engineering and Maintenance-of-Way Association] has specifications to be qualified as a tie,” Musazay says.

“If you start with a plastic, most of the time, it will not meet the requirements,” he continues. “There is a dimensional requirement that is the shape, regardless of the material, and then there are requirements for a number of engineering properties that quantify the ties’ strength, resilience, and durability. Then there is a test for each and every one of the properties, and they have to meet a certain number before they are qualified as railroad ties. If they don’t meet those limiting criteria, they don’t qualify as ties.”

The researchers have made sure to avoid that problem. “We used 100 percent recycled materials,” which, Musazay says, “can meet the engineering requirements” for railroad ties. With a plastic tie, “you will have a lot of benefits compared to concrete or wood. If you look at it from the environmental point of view, one mile of a single track has between 3,150 and 3,350 wood ties, depending on typical wood tie spacing, which could be 19 or 20 inches center to center. Concrete ties have different spacing, about 24–25 inches. But we compare our product in terms of wood ties. To have that many ties from wood, you have to cut 700–900 trees. If you want to make the same out of plastic bags, you can average 10 million plastic bags.”

Huang explains some of the decisions the researchers made based on practical considerations. “We propose using recycled plastic not for longevity” because they do fail. However, “recycled plastic you can reclaim and heat up,” making new ties. “But obviously recycled ties are softer,” he says. While concrete ties would be “a nice alternative, if you can afford it, but once they crack, there’s no way to repair them. It’s also very difficult to put the sensors into concrete.”

To make the ties, the researchers reached out to Eco Plastic Products, a nonprofit company in Delaware that donated waste plastics to the project. “We have weekly meetings with them,” Musazay says. “We discuss formulas and designs and what has to change. They then make the ties in their Wilmington facility and ship them to us for testing at the University Park campus.”

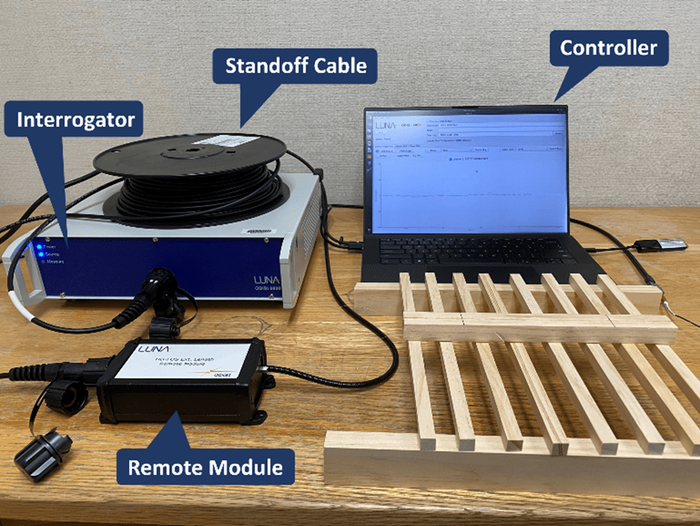

Testing setup showing how the strain data is collected

Once the railroad ties are formed and high-definition distributed fiber optic strain sensors are added, testing begins. The researchers want to see if the sensors can identify weaknesses under the ties. “My part of the project primarily involves collecting the strain data of the composite tie and developing an algorithm to predict poor support conditions,” Zhou says. It is important to have information from all along the tie, not just on an end or in the middle, he notes. “The strain sensor was instrumented along the entire composite tie so that the strain profiles under different support scenarios were collected. Poor support conditions—such as loss of ballast and uneven support—could be recognized by the proposed algorithm.”

Fourteen Penn State Altoona students, including Yoder, attended the 2022 AREMA conference. The recycled ties research project was recognized as “Best in Show” in the Student Showcase. Not a bad outcome for a student who didn’t foresee himself working on research projects when he first came to Altoona. But when Shen asked the class, he was in if anyone was interested in joining the project. “Nobody stepped forward,” Yoder says. “Something in the back of my head said, ‘do it.’” He admits, “I came into it with a skeptical mindset. I didn’t think I would like it, but I loved it.” He had made the assumption, as so many students do before they try it, that “research would be uninteresting. But seeing it from a laboratory point of view is very interesting.”

The professors are optimistic about the future of the project. Shen says the tie they’ve been working with is a “small sample that is to be tested for AREMA’s specs.” The next step is to test a “real-size sample, 8.5 feet long, 9 inches wide, 7 inches thick,” which has been made by Eco Plastic Products based on the research designs. Huang adds, “These ties are cost-effective, durable, and able to sense. That’s where we are. We are conducting tests in the next couple months, and then we will test in the real-world environment.”