This 1942 U.S. Army photo shows a typical field pharmacy that chemists like Hengst worked in.

Growing up in the rural village of Sproul, Pennsylvania, during the Great Depression, Clarence W. Hengst could hardly have imagined working in a land 8,000 miles away. The Second World War would afford him that unexpected opportunity.

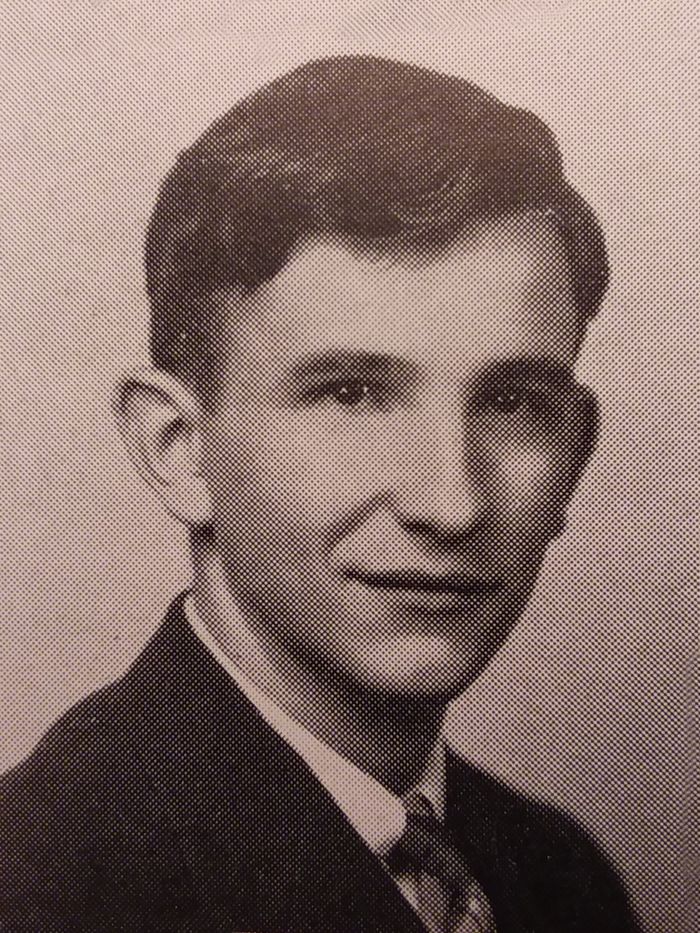

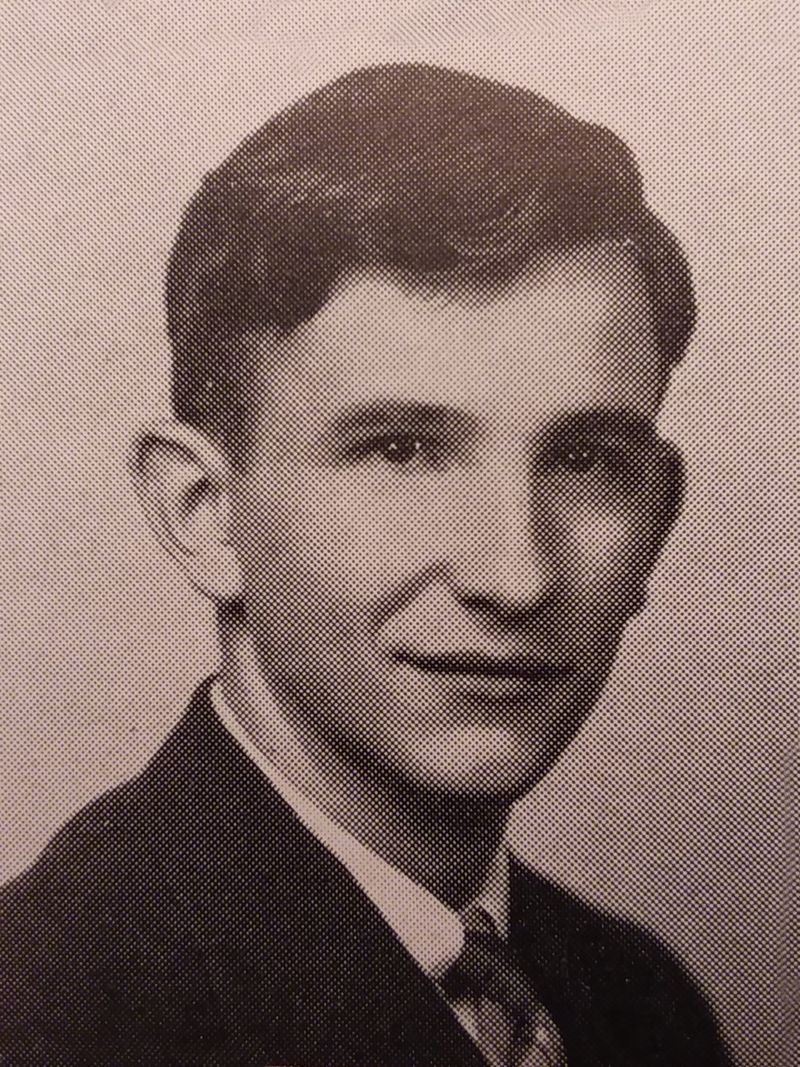

Hengst enrolled at Penn State Altoona -- then known as the Altoona Undergraduate Center (AUC) -- when it opened in September 1939—the same month World War II erupted in Europe. Wishing to build upon his existing expertise in the realm of heavy industry, Hengst excelled in his studies of chemistry and geology. Simultaneous to his academic achievements, he engaged in multiple extracurricular activities, including the College Chess Club and the Altoona Undergraduate Center Band. After two years of study at Penn State Altoona, Hengst transferred to University Park, obtaining his bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1943.

In the wartime economy, college students were often spared from the national draft so their talents could be put to use in the corporate world. Henst thus entered the workforce and not the military. His new place of employment was a Celanese Corporation of America plant, located in Cumberland, Maryland. The factory produced various forms of synthetic fiber and yarn. In peacetime, the company had marketed its synthetic silk to housewives. Now, Celanese was producing parachutes and related military necessities.

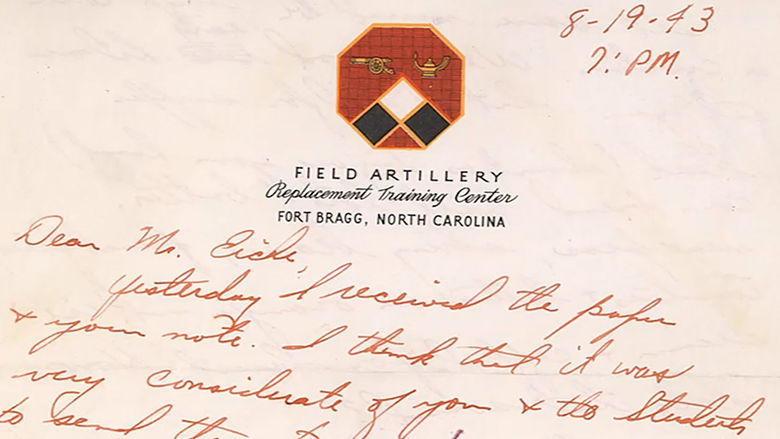

During the war, Penn State Altoona campus director Robert Eiche maintained a vibrant correspondence with his former students. He saved over 500 of their wartime letters—including those from Hengst. Hengst wrote to Eiche on Jan. 1, 1944: “I have really enjoyed receiving the newspapers from dear old AUC. When I read over the paper, I can still imagine myself dashing up and down stairs and rushing across town from Webster to Madison (buildings) or back again. I am glad to hear that the enrollment at AUC is picking up. I hope that we will always have an AUC and I know that without it many of us would have been unable to secure a college education.” Like many other letters written to Eiche, the students expressed their earnest appreciation of higher education. (The letters are now archived at Penn State Altoona’s library named in Eiche’s honor.)

During the first two and half years of the war, Hengst continued his work in Cumberland. He was finally drafted into the armed forces in June 1944. Military service ran deeply within the Hengst family tradition. His grandfather served in the Civil War and his father in World War I. Hengst swore his oath of enlistment on June 21, 1944, only two weeks after the commencement of the Normandy invasion. Hengst was among 71 men from Altoona and Blair County to depart for the U.S. Army on June 26.

Hengst’s enlistment records placed him within the occupational category of chemists, assayers and metallurgists— a minority within the lesser educated GI population. Even so, Hengst was immersed in basic training at Camp Barkeley, Texas, that summer. Fellow trainee George Mandler described the lonely camp near Abilene as “surrounded by red dust and mud, which made the officers’ white-glove inspections of our huts very perilous. Abilene had few saving graces.” But not all was dreary. Another GI referred to Abilene as a “paradise” getaway that allowed troops to blow steam and paychecks. Even though the town clung to the traditions of Prohibition as a “dry” town, the sudden influx of soldiers prompted a spike in sales of “medicinal alcohol” at local pharmacies. Meanwhile, the marriage rates among local young ladies rose dramatically. Abilene became something akin to a Wild West boomtown again.

Being so far from home, Hengst took comfort in his ongoing correspondence with Eiche. His professor’s letters “brought back some very pleasant memories of Altoona and State College. . . . I received a copy of the Penn State Collegian last week and shared it with another Penn State man in my hut. He seemed to enjoy it even more than I did because many of his personal friends were mentioned in it. I’ll share your letter with him; I think he’ll enjoy it too.”

Less than five months later, Hengst arrived in the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater following his promotion to corporal. His new post: Calcutta, India. By the time of Hengst’s entry into the service, the ancient metropolis had evolved into one of the largest cargo centers in the world. Earlier in the war, fears of the Japanese seizing northeast India manifested following the attacks on Pearl Harbor and the Philippines. Such a move would have further cut off the already besieged Chinese. American presence in India thereafter grew. In the initial phases of the conflict, the Allies utilized the Burma Road, a transportation artery that funneled over 20,000 tons of supplies every month into China. Following the 1942 capitulation of Burma, an alternative transportation route was required posthaste.

The solution was flying the “Hump,” a strenuous flight path of 525 miles over the Himalayas, connecting India and China. As Life magazine declared, “Born out of confusion and chaos, it barnstormed its way to maturity and now performs its missions with a streamlined efficiency that has profound significance for the postwar world. It has, above all, kept China alive.” One sergeant stationed in India seconded that notion by stating, “Calcutta was where the flyboys would take off over the Hump into Kunming, drop off their supplies and return home. This was a milk run for them. They were supplying whatever their airplanes could carry.” Despite this assurance, flying cargo planes over the Himalayas was anything but easy or safe.

Hengst’s home away from home was known simply as Base Section, a major supply depot in the multinational operation. Located along the Hooghly River, the dully-named installation was one of the busiest ports in the world. Overcoming humidity, malaria, and acclimation to Indian culture, American personnel near Calcutta forged a lasting imprint on the war effort. Scores of barges sailed in daily with cargo loads nearly incomprehensible in scale. From mid- to late-March 1945 alone, Base Section processed some 114,000 tons of war materiel, vehicles, and food for distribution. In a guidebook issued to American service members in Calcutta, one general warned, “It is part of your job to cultivate a lasting relationship with India. . . . You are a possible friend—a hope for the future.”

Serving as a pharmaceutical laboratory technician with a medical unit, Hengst utilized his knowledge of chemistry and corporate efficiency. According to one Altoona Mirror article, Hengst’s unit "led military installations throughout the world with material and medical aid.” The colossal effort was one of the great logistical undertakings of the war. Eventually promoted to first sergeant and appointed to Headquarters Company at Base Section, Hengst served as one of many gears in a vast machine. A June 29, 1945, letter from Hengst to Eiche was partially redacted by military censors but concluded, “I no longer help bomb Japan. I’m still working as a laboratory technician and I find it very interesting, but it’s chemistry for me when the war’s over.”

Hengst served 16 months overseas. By early 1946—with the war won—Base Section was no longer deemed a necessity. The United States prepared for its departure from India, with British colonizers finally following suit the next year. In his last weeks of deployment, Hengst supervised the transfer of equipment and mountains of red tape. Coincidentally, fellow Blair County native Thomas C. Datres of Altoona worked by his side. As their local newspaper reported, the two soldiers “were members of the American forces who remained in India to complete the closing mission of the theater.” The China-Burma-India Theater was officially deactivated on May 31, 1946. That same day, Hengst and Datres embarked on their lengthy voyage to San Francisco on the SS Marine Jumper, the last U.S. vessel to depart India. Taking in the view of the Golden Gate Bridge was a welcoming sight. Seeing Blair County after two years away was an even grander one.

Like many veterans, Hengst started a family after the war. He also rose through the ranks of the regional chemistry industry and was appointed a manager at Garland Petroleum. Even as Hengst’s World War II experiences grew increasingly distant, his ties with the military community remained. He returned to the service during the Korean War and was a lifelong member of the Hyndman, Pennsylvania, chapter of the Veterans of Foreign Wars. His commitment remained steadfast until his death on July 11, 1999, at age 78. He was laid to rest with full military honors.

Thousands of Penn Staters served in the Second World War. At least 375 of them did not return. Clarence Hengst felt blessed to have survived the costliest conflict in human history.

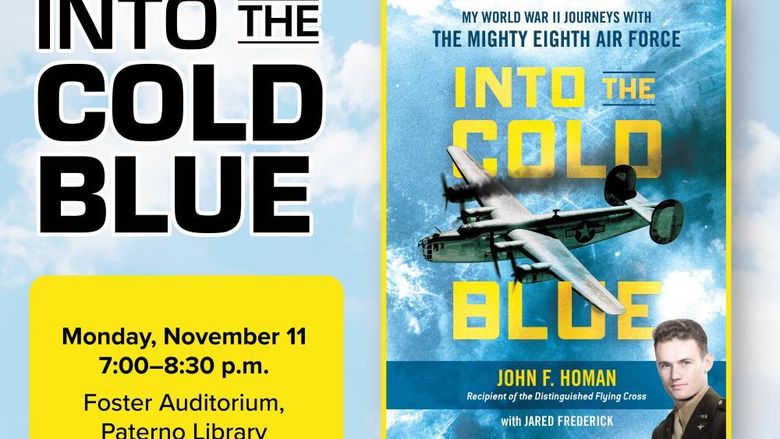

Penn State has a longstanding and proud tradition of serving the men and women of our military through education benefits, resources, support and more. This year's Military Appreciation Week from Nov. 8 to 16 will honor America's "Greatest Generation" with a weeklong series of campus events, including a football game, Veterans Day ceremony, speaker series and more. Visit militaryappreciation.psu.edu to learn more.